Poison (3 page)

Authors: Jon Wells

A forensic pathologist is the death sleuth. It is the coroner, however, who is the public’s representative for questionable or sudden deaths, deciding how to proceed in the early hours of an investigation. But the coroner is not necessarily an expert in death. In Ontario, he is typically a family doctor doing coroner work on the side, one of 400 or so in the province paid a flat $250 per case. Dr. Bashir Khambalia, a family physician in Hamilton’s east end, was the reporting coroner when Parvesh Dhillon died. He was born in Zanzibar, an island off the coast of East Africa. In 1963, the year the island gained independence as a British protectorate, he left for medical school in Ireland. Khambalia, 50, was fluent in Gujarati, a western Indian dialect. Starting in 1995, he had handled about 200 coroner’s cases a year as an Ontario coroner over a period of three years.

It is up to the attending hospital doctor to decide if a death should be referred to the coroner. Dr. Mary Devlin had treated Parvesh in hospital, was mystified by her death, and asked the chief neurologist for his opinion. His best guess was a massive seizure leading to cardiac arrest. But the constant muscle spasms and rigidity were unusual. Devlin called Khambalia soon after she was pronounced dead. He visited the morgue to view the body and decide what to do next. Hospital charts documented her final moments, included notes from residents, doctors, and nurses who logged in comments at specific times during her stay.

A coroner is not required to examine the notes, but it is normal practice to do so.

A coroner is not required to examine the notes, but it is normal practice to do so.

Monday, January 30 Nurse notes: Family reports Parvesh Dhillon ingested two capsules of Fiorinal C1/4 given by a family member. Soon after, body observed to exhibit rigidity, including an opisthotonic position lying on the floor. Family reports clenched teeth. Loss of consciousness, fell to the floor. Ambulance at scene at 16:20, approx. 20 minutes after the episode, found her lying in the rec room. No pulse, skin warm, cyanotic. No respiration, no blood pressure. Patient resuscitated and transported to Hamilton General.

In E.R.: dilated fixed pupils, jerky movements in both arms. Treatment: midazolam, dextrose in water, naloxone.

In ICU: subsequent to resuscitation, frequent myoclonic jerking, increased muscle tone and reflexes. Treatment: midazolam, vecuronium. Lab report: severe acidosis, elevated blood lactate level. Difficult to ventilate due to seizures. Tox screen: absence of barbiturates, acetone, ethanol, ethylene glycol, isopropanol, methanol, phenobarbital, and salicylate. 21:00: myoglobinuria.

Tuesday, January 31

07:00: patient has spontaneous twitching. 08:00 body spontaneously jerking. Neurological assessment at 11:30: increased muscle tone but has myocloni-spasmatic -response to facial stimulation. 19:40 patient has brisk flexion of all limbs in response to stimuli.

07:00: patient has spontaneous twitching. 08:00 body spontaneously jerking. Neurological assessment at 11:30: increased muscle tone but has myocloni-spasmatic -response to facial stimulation. 19:40 patient has brisk flexion of all limbs in response to stimuli.

Wednesday, February 1

CT scan 18:30. Normal.

CT scan 18:30. Normal.

Thursday, February 2

Neurology note: second CT scan of head shows subarachnoid hemorrhage, edema, transtentorial herniation.

Neurology note: second CT scan of head shows subarachnoid hemorrhage, edema, transtentorial herniation.

Friday, February 3

Ms. Dhillon pronounced dead at 10:30.

Ms. Dhillon pronounced dead at 10:30.

Hospital staff had never seen anything like it, a woman so horribly sick for no apparent reason, and they’d never seen seizures like that. Parvesh was “cyanotic” in her home, meaning her skin turned blue. The reference in the notes to “myoglobinuria” meant that Parvesh had spasmed so violently, and continually, that cells from her overworked, shredded muscle fiber were found in her urine, which became the color of tea. “Acidosis” referred to high acidity in the muscles from overuse, a pH level of 6.75, the worst doctors had seen in a patient who was still alive. Her muscles produced so much lactic acid that her blood lactate level hit 10.6, when the upper limit in most patients is 2. It was the highest the ER doctors had ever seen.

There were two critical bits of information in the notes. The first was the description of Parvesh’s severe rigidity and “opisthotonic” state. The word was scribbled messily on one of the notes. It meant that her back was severely arched—an unusual condition. The second was the hospital’s own limited drug screen, given to Parvesh upon her arrival, which showed no barbiturates in her blood, even though an earlier note said her husband reported that she had taken two prescription Fiorinal headache capsules, which are barbiturates. Those facts were contradictory. The staff report concluded that Parvesh died of natural but unexplainable causes.

Khambalia ordered an autopsy. It was a routine decision. Going that far was accepted protocol in 1995 for the sudden death of a young adult. If a coroner does not report a death to police, they do

not get involved. There is an office in the Hamilton Police Service that liaises with the coroner, but it is up to the coroner to make the call. Khambalia ordered no further testing of Parvesh’s blood or body tissue. He ordered nothing sent to the Centre of Forensic Sciences in Toronto for a more detailed toxicology screen. One day, coroners would be required to phone police and order blood screens for any questionable sudden death. Khambalia, trained as a family doctor, was following accepted procedure in 1995 and there were no alarm bells going off anywhere. Even seasoned specialists did not make the connections in Parvesh’s death.

not get involved. There is an office in the Hamilton Police Service that liaises with the coroner, but it is up to the coroner to make the call. Khambalia ordered no further testing of Parvesh’s blood or body tissue. He ordered nothing sent to the Centre of Forensic Sciences in Toronto for a more detailed toxicology screen. One day, coroners would be required to phone police and order blood screens for any questionable sudden death. Khambalia, trained as a family doctor, was following accepted procedure in 1995 and there were no alarm bells going off anywhere. Even seasoned specialists did not make the connections in Parvesh’s death.

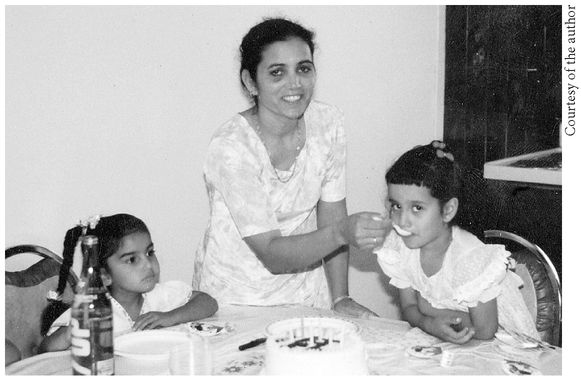

The Sikh woman bathed the body then rubbed white yogurt over the pale, cool skin of Parvesh Dhillon. Later the woman dressed her in Parvesh’s finest clothes, a rose-colored dress, the head and hair covered. The funeral was February 8. The morning broke bitterly cold, winds whipping off Lake Ontario, the water charcoal beneath the ashen sky. Inside the Donald Brown Funeral Home on Lake Avenue in east Hamilton, Parvesh lay in an open casket. Even in death her face was radiant. The sobs of Parvesh’s daughters, Aman, seven, and Harpreet, nine, accompanied the priest’s Sikh readings.

Parvesh and her daughters, Aman (left) and Harpreet

Other books

The Pregnant Bride by Catherine Spencer

The History of Jazz by Ted Gioia

DarkStar Running (Living on the Run Book 2) by Ben Patterson

Nairobi Heat by Mukoma Wa Ngugi

Forsaken Soul by Priscilla Royal

Alta fidelidad by Nick Hornby

True Believers by Jane Haddam

Tales of the Out & the Gone by Imamu Amiri Baraka

Her Charming Heartbreaker by Sonia Parin