Poison (4 page)

Authors: Jon Wells

God is only One, He is obtained by the Grace of the True Guru/In whatever house meditation on God is practiced and His praises are sung.

Sing His praises and meditate upon Him in that house/You, please, sing the praises of my God, the Fearless/I am a sacrifice to the Song which gives perpetual peace.

Sikhs cremate their dead; the body is just a vessel of water and air. There is earthly reincarnation of the soul—but only for sinners. The goal for the just soul is to return to God at death, as one began at birth, to avoid the toil of hell on earth. The priest prays for the soul of the dead: forgive the deceased of sin; keep the soul with God always.

On the other side of Hamilton Harbor, across the Skyway bridge, past billowing smoke and lapping flames of steel mills, sat Bayview Crematorium. The casket arrived that afternoon, was carried into the chapel room. More prayers. The oven—what crematory officials call the “crematory retort”—was heard humming across the hall. The burner incinerates the casket and all contents. Afterward, brass fixtures and screws are separated, and surviving bones pulverized in a blender-like machine, then added to the ashes.

In Indian culture, sons are revered. And so, at a cremation, it is the eldest son of the deceased who pushes the burner switch. But Parvesh never had a boy. That meant it was up to her husband to do it. Sukhwinder Dhillon. His middle name was Singh, like most Sikh men, a symbol of the fundamental Sikh belief opposing the Hindu caste system, so that all should carry the same name to illustrate equality. Singh, in English, means lion. Another tenet of Sikhism is respect for women, especially your wife.

Dhillon and the other Sikh men carried the casket holding Parvesh from the chapel area to the brass door with the cross inscribed on it, then into the burner room. A wall of dry heat hit their faces, as though in a boiler room, the burner droning loudly. They lifted the casket, slid it into the burner. The black iron door shut. There was a tiny round window through which the orange

flame was visible. The button on the wall was labeled “primary burner.” Dhillon placed his thick finger on it and pushed, igniting 2,000 degrees of heat to swallow Parvesh’s body. Dhillon left his wife’s ashes at the crematory in a plain box with instructions that they be mailed to her brother, Seva, in India. His treatment of the ashes was, in Sikh culture, blasphemous, equivalent to a Christian urinating on a loved one’s grave. A few days later Dhillon heard the voice on the phone from overseas shake with rage.

flame was visible. The button on the wall was labeled “primary burner.” Dhillon placed his thick finger on it and pushed, igniting 2,000 degrees of heat to swallow Parvesh’s body. Dhillon left his wife’s ashes at the crematory in a plain box with instructions that they be mailed to her brother, Seva, in India. His treatment of the ashes was, in Sikh culture, blasphemous, equivalent to a Christian urinating on a loved one’s grave. A few days later Dhillon heard the voice on the phone from overseas shake with rage.

“Dhillon, if you have done anything to my sister, anything, I swear—” Seva, usually a warm, quiet man, was yelling now. The normally serene green eyes he shared with his sister burned. He knew Dhillon. Did not trust him.

“Veerji!” Dhillon interrupted, using a Punjabi term of affection that means brother. “I didn’t do anything!”

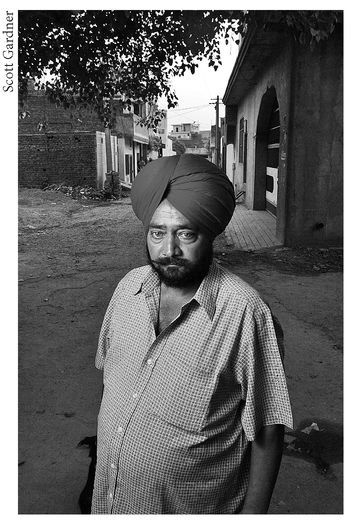

Seva Singh Grewal, Parvesh’s brother, at home in Ludhiana, India

“If you have, I will get you. I will see to that, I promise you.”

With time, Seva’s anger would fade, but sorrow never left him—sorrow and confusion. “Why, God?” Seva asked in prayer the day he took his sister’s ashes to the holy Sutlej River at Kiratpur Sahib. “Why did you take her?”

CHAPTER 2

CHASING DEMONS

Hamilton, Ontario

1967

1967

The little boy’s liquid-blue eyes stared out the car window. His dad, Maurice Korol, had parked his white Ford Meteor on the street in front of Mike and Sally’s house on West 1st in Hamilton. Warren was six years old. Something was wrong. A pile of lumber, dumped right in the middle of Uncle Mike and Aunt Sally’s driveway. What was that all about? And why did Aunt Sally look so upset? When Warren got a bit older he learned the truth. The unsolicited delivery was mob harassment. Big Uncle Mike Pauloski was a Hamilton cop, and the delivery was courtesy of one of Johnny “Pops” Papalia’s goons.

Aunt Sally would receive crank phone calls late at night when Mike was on the clock. “I’m sorry to inform you, miss,” the rough-edged voice began, “that Mike Pauloski’s body is in the morgue.” And then the next day, funereal flower arrangements arrived at the house, the card reading, “In Memory of Mike Pauloski.” Black humor from Papalia, The Enforcer, Steeltown’s most notorious Mafia chief. Or perhaps a chilling prophecy.

One time, Mike was actually home and answered the phone. “It’s Pauloski,” he growled. “I swear I won’t rest until your balls are hanging on display.”

He wasn’t just any cop, but a famous cop in a time when cops were famous, founder of the Hamilton Police “morality squad.” Big Mike, six-foot-four, 265 pounds, drove around Hamilton in a bread truck with spy holes cut out. He helped nail Papalia on the French Connection deal. Pauloski and his partner, Albert Welsh, showed up in New York City for the godfather’s trial, and the sight of the pair in court enraged Pops.

Each year at the annual Hamilton Shriners parade, Mike led the way, holding aloft a sword. Standing in the crowd, front row, wide-eyed, worshipping Big Mike, was little Warren, his nephew, the glory of being a cop branded on his soul. In 1972, when Warren was 11, his uncle died young, killed by a drunk driver on Upper

James Street. Mobsters crashed the funeral. Could it be that their arch-enemy was really dead? No, the mob didn’t kill Uncle Mike, but Warren never forgot, nor forgave, that bastard Papalia, who, years later, much to his chagrin, survived into old age, attaining a kind of grandfatherly celebrity aura in Hamilton.

James Street. Mobsters crashed the funeral. Could it be that their arch-enemy was really dead? No, the mob didn’t kill Uncle Mike, but Warren never forgot, nor forgave, that bastard Papalia, who, years later, much to his chagrin, survived into old age, attaining a kind of grandfatherly celebrity aura in Hamilton.

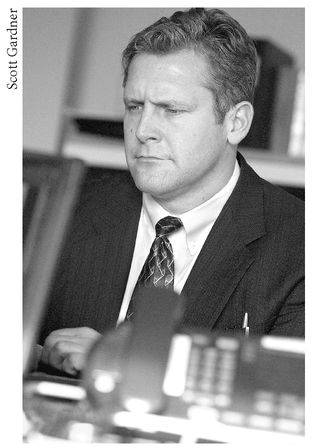

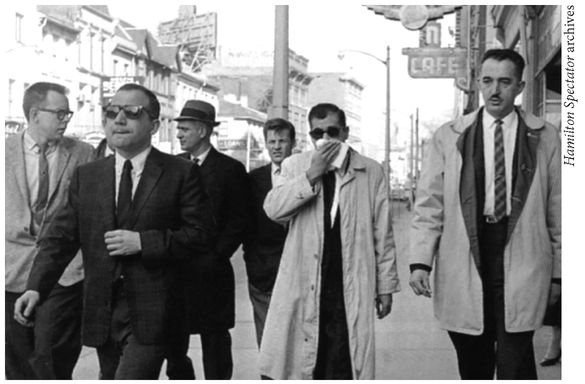

Warren Korol

Twenty-four years later, in September 1996, the broad-shouldered homicide detective stared at the glowing screen of his computer with eyes that had a metallic core outlined by a ring of propane-flame blue. Warren Korol. On his office wall hung a framed old newspaper photo, black and white, just like the morality of the time. The photo showed Johnny Papalia, in flowing trench coat and dark glasses, holding a handkerchief over his mouth to hide from cameras, escorted along downtown King Street by plainclothes detectives and a couple of jacket-and-tie-wearing reporters. The tall cop at the far right side of the frame was Mike Pauloski. The photo inspired Warren Korol—big Mike and, in a different way, Pops himself, two symbols forever joined. The good and the bad. One to emulate, the other to pursue.

Hard to believe, but in 1996, at 35, Korol had already been a cop for nearly half his life. He started on the force in the cadet program at 18 when he was still playing football for the Hamilton Hurricanes. He graduated to officer status at 21. And now, as a plainclothes detective in the homicide branch, called Major Crimes, he had yet to tackle a high-profile case. That would all soon change. The cursor hopped across the computer screen as his fingers tapped at the keys:

I, Warren Korol, of the City of Hamilton, in the Province of Ontario am a Peace Officer employed by the Hamilton Police Service, working out of the Major Crime unit and I hold the rank of Detective.

Mike Pauloski (far right) escorts Johnny Papalia (handkerchief over face) downtown.

His late father Maurice was a hard-working, driven man who moved the family out west, toiled in the fishery and as a lumberjack before heading back east to Hamilton where jobs seemed more plentiful. Warren had not faced similar odds, so sought other challenges. Nobody in his family had a university degree. He would make that happen, one day. Korol, while still physically imposing, had carried 255 pounds on a six-foot-two frame until he decided change was in order and sheared 40 pounds.

Policing ran in his blood and, from the start, he wanted to work in homicide. Could there be a bigger challenge than chasing murder cases, serving as emissary for the living and the dead? Korol’s ice cool was made for detective work. He emanated an easy, “hey-how-ya-doin’?” manner that put others at ease, with an omnipresent smirk and smiling eyes. Those around him reveled in sharing his confident glow. Korol seemed the type that, even after a day following death and chasing demons, would sleep soundly at night, comfortable in his own skin.

But working homicide carries a price: witnessing, up close, gaping bullet holes in skulls; finding a woman still wearing a white satin nightie in a ditch, body so decomposed identification seems impossible. Worst of all were the kids. They are the pure victims. Korol struggled with these experiences the most: a child shaken to death by a parent; meeting the three-year-old boy who spent a night in his house with the bloodied corpses of his dead mother and her boyfriend; Korol’s first child autopsy, seeing a kid similar to his own three little ones split open on a metal table in the morgue. Then another, and another, five, ten, maybe 20 child postmortems by now. He didn’t like to think of the numbers.

In a sense, by the fall of 1996, Warren Korol’s best days on the job were behind him—the early smashmouth days as a raw, brash uniformed cop. Korol, barely out of his teens and still playing defensive line in football part time, gleefully drove around downtown in the paddy wagon. Hell, that was when you could still call the paddy wagon a paddy wagon and have no fear of offending politically correct sensibilities. Great days. On patrol Korol could enter a downtown bar at closing time, confront an unruly drunk, take a punch in the face, feel his cheekbones sink, eyes losing focus, pain flowing down the spine to the ankles. In those days he could reply in kind, and then some, with no fear that some gang punk would pull a gun or bury a machete blade in his skull, or that Korol himself would be convicted of assault.

Korol’s philosophy was, what would the public expect of him? He was certain they would expect him to hit back when warranted. That’s what happened one night at Hanrahan’s when he worked vice and drugs. Korol split the curtain of cigaret smoke in the cave-like gloom of the Barton Street strip club, women on stage named Kenya and Montana gyrating before the vacant stares of the regular patrons. He approached a group of hard-faced dancers, their skin darkened and lingerie-themed costumes glowing under black light. He read a dancer her rights on a drug arrest. Suddenly his vision went black as a woman’s fingernails gouged his eyes, attacking him from behind, he tasted blood as the nails slipped lower into his mouth, tearing

at his gums. He wheeled and punched her in the face, dropping her instantly.

at his gums. He wheeled and punched her in the face, dropping her instantly.

“We don’t expect our police officers to pick fights,” intoned a judge weeks later in court, addressing the stripper’s defense lawyer, who had—with the kind of chutzpah that keeps the lawyer joke industry humming—tried to bring the police brutality book down on Korol. “But when our police officers do get in a fight, we don’t expect them to lose.” Korol sat there, unsuccessfully stopping his smirk from breaking into a full grin. Not guilty.

The keyboard clicked as Detective Warren Korol continued typing:

I have personal knowledge of the facts hereinafter reported except where same are stated to be based upon information and belief.

In a high school life of forgotten quadratic equations and African river names, Grade 9 touch-typing was the best course he ever took. Sixty-four words a minute by summertime, and he could still hear the distinctive sound: clack-clack-clack. fff-jjj-fff-jjj. All the laborious drills on the old manual typewriters where you slammed ink-stained keys into paper.

Other books

Zombie Outbreak by Del Toro, John

Charmed and Dangerous by Lori Wilde

The Haunting of Highdown Hall by Shani Struthers

Connie’s Courage by Groves, Annie

Harry's Sacrifice by Bianca D'Arc

A Shift in the Air by Patricia D. Eddy

The Fallen by Charlie Higson

The Mapkeeper and the Rise of the Wardens by Katie Cash

Establishment by Howard Fast