Poison (2 page)

Authors: Jon Wells

Parvesh Dhillon was a beautiful woman. Fragile smile, a gentle, regal aura, and skin that was a pale tan, like wood leached of its color by storms. Her teardrop-shaped eyes looked pale blue at first. No, they were more a drained aqua. The color seemed in the eye of

the beholder, as though framed by the setting, the way water captures a sky’s dark ceiling, golden dawn or dying blue, red and gray at sunset.

the beholder, as though framed by the setting, the way water captures a sky’s dark ceiling, golden dawn or dying blue, red and gray at sunset.

The odds were very much against Parvesh living at all. She grew up on the other side of the world in the Punjab, a male-dominated, son-revering culture. She was the first girl born and kept in her family in generations. Sikhs believe God wills everyone’s life story. What would Parvesh’s story be?

The brush gently tugged at the scalp, kneading her neck, a hypnotic massage. She savored the moment, sighed deeply, eyes shut, muscles loose. Her hair dry and ready to be tied, the rest of her day, and life, beckoned.

Teeth and fists clenched, it felt like every muscle flexed without pause, as though a bolt of lightning ripped through her spinal cord, igniting every fiber, raping the nervous system. Worst of all, Parvesh Dhillon had horrifying clarity of mind, intensified with a sense of dread. She saw her fate rush toward her like a train’s light in a black tunnel.

“I am—dying,” she moaned.

Senses on fire, eyes stung by blinding white light, ears ringing with the voices of gathered family members shouting her name. It was Monday, dinnertime. Parvesh lay on the living room rug but only her heels and back of her head touched the floor. Her back arched, every muscle contracting violently, teeth pressed together as though in a vise, freezing her face in a grotesque mask.

Risus sardonicus

was the Latin name the old forensic pathologists gave it: The sardonic smile. The death grin.

Risus sardonicus

was the Latin name the old forensic pathologists gave it: The sardonic smile. The death grin.

The Dhillons lived in Hamilton’s east end, a suburb called Stoney Creek. Next door, Olga Vidal spread tomato sauce on homemade dough, added cheese, olives, and pepperoni. A panicked knock at the door. Olga’s teenage daughter answered. It was Aman, Parvesh Dhillon’s seven-year-old daughter. Her eyes were red and wet.

“My mom is dying!” Aman screamed. The teenager laughed, thinking Aman was joking. Aman ran past her to the kitchen.

“Don’t say that, dear,” Olga said.

Aman ran back out of the house, and Olga followed her next door. Inside the Dhillons’ home, she saw her friend convulsing on the floor, spine bent, as though possessed by an evil spirit. The husband, Sukhwinder, called to his wife. “Parvesh! Parvesh!”

In Parvesh’s state, sounds exploded in her ears, every sensation knifing sensors in the brain. Sukhwinder lowered a glass of water to her mouth, the water singeing her lips like molten steel. Olga dropped to her knees, gently taking Parvesh’s foot in her hand, rubbing it, trying to bring comfort, but it only encouraged spasms.

Her stomach swelled like a balloon, then deflated. The aqua eyes focused on Olga, a light of recognition flashed. Parvesh tried to tell her something, tried so hard to process a signal from her oxygen-starved brain. A deep moan came from the back of her throat.

Soon she was, mercifully, nearly unconscious, her breathing labored, pale eyes flickering. The firefighters were there first, then a paramedic named Stephen Bell. A young woman, fingers clenched like talons; arched back, lips peeled back over gums in a sick grimace. En route to Hamilton General Hospital downtown, tight straps on trembling arms. Chest compressions. Two electric shocks from the life pack. Her eyelids quivered.

There was a chance, perhaps, to save her, but neither paramedics nor hospital staff had ever seen symptoms like this before. An immediate, strong dose of Valium or an anticonvulsant would help. A neuromuscular blocking agent could induce temporary paralysis by halting the extreme signals sent to muscles by her brain.

At the General she was placed on life support.

For the next four days she lay unconscious, displaying occasional muscle seizures and twitching. Perhaps Parvesh could still dream, her soul sweeping back home to the Punjab and the place called Kiratpur Sahib, ripples dancing in the Sutlej River, the water a green-gold in dying sunlight, surrounded by fields of elephant grass and sugar cane leaning with the wind. A verdant, tropical place invoking life—and death. It is the holy place where Sikhs sprinkle the ashes of their dead into water that is still and soft, warm to the touch. Then she glimpses the end of her golden dream, sees the orange inferno behind the iron door just as it

slams shut, hears her brother weeping in the thick hot air at the river’s edge.

slams shut, hears her brother weeping in the thick hot air at the river’s edge.

Sikhs sprinkle ashes in the Sutlej River.

In the hospital, Parvesh’s husband, Sukhwinder, gave his approval to remove her from life support on February 3. The four-day time lag from her collapse to death was unusual. Victims of that particularly exotic terror usually die within minutes, a few hours at most. But she wouldn’t let go. Parvesh is a Punjabi name that means “entry.” Parvesh had not been ready to exit this world, whatever the will of God. Or her killer.

Hamilton General Hospital

Forensic Pathology Department

Forensic Pathology Department

The body lay on the cold metal table, the thick antiseptic odor of formaldehyde filling the air. Forensic pathologist Dr. David King began the autopsy. There was little blood; corpses don’t bleed. It is protocol for a homicide detective investigating a murder to attend the autopsy, answer the forensic pathologist’s questions, take notes. For a young or green cop, it can be difficult to stomach.

Years ago, when lax rules allowed for such things, detectives lit up cigars in the autopsy room to mask the scent of death. But there was no police officer in the room at Parvesh Dhillon’s autopsy. Police had not been called to investigate. The case belonged to David King alone.

Years ago, when lax rules allowed for such things, detectives lit up cigars in the autopsy room to mask the scent of death. But there was no police officer in the room at Parvesh Dhillon’s autopsy. Police had not been called to investigate. The case belonged to David King alone.

King, a slight, silver-haired man with round eyes, took the electric saw in his hand, the circular blade rotating into a blur. To the unschooled eye, an autopsy strips the human body of all mystery. The autopsy may seem an open book thanks to Hollywood; the camera cutting in and out, flashing glimpses of tissue here, a bullet hole there. In the real world the autopsy exists behind a curtain. Forensic pathologists prefer it that way. It is science they are engaged in, science of the most important kind: science in pursuit of a killer’s fingerprints. But they know that, to the untrained eye, the autopsy flashes a rude fluorescent light on our own mortality. The cadaver is made hollow, the internal wiring exposed, handled, prodded, diced. Tissues, valves, membranes, skin, bone. If there is a soul, a self, it is not here, not anymore. To pull back that curtain for the public, they fear, would put the practice itself at risk.

Dr. David King, forensic pathologist

At 65 years old, David King was retired. Technically he was, anyway, but forensic pathologists with his experience and professional memory were rare. He had a national reputation. Until a replacement was found, he agreed to stay on the job at Hamilton General. Why had this young woman died so suddenly, violently, without explanation? King examined Parvesh’s heart. There appeared to be no disease, no scarring. With a large knife he carved off pieces of organs, including

the liver, the organ that holds poison and drugs the longest. As he cut, he deposited bits of tissue into small plastic containers of fixing formula, so the samples would later harden, allowing him to slice thin layers for microscopic examination. He noticed that on Parvesh’s hospital chart, staff had, as a matter of protocol, screened her blood for drugs and found nothing. But he also knew the hospital screen was limited in scope, unlike a detailed toxicology screen that can detect more than 100 drugs, poisons, and other compounds.

the liver, the organ that holds poison and drugs the longest. As he cut, he deposited bits of tissue into small plastic containers of fixing formula, so the samples would later harden, allowing him to slice thin layers for microscopic examination. He noticed that on Parvesh’s hospital chart, staff had, as a matter of protocol, screened her blood for drugs and found nothing. But he also knew the hospital screen was limited in scope, unlike a detailed toxicology screen that can detect more than 100 drugs, poisons, and other compounds.

Poisoning is the most difficult homicide to detect and prosecute, which is the reason poisoners get away with murder more than other killers. And they are among the most difficult cases a forensic pathologist encounters. There are those rare occasions, certainly, when a quick glance at a victim can tell the tale: hair loss points to the presence of thallium and other heavy metals; constricted pupils to opiates and pesticides; garlic odor to arsenic; almond odor to cyanide; shoe polish odor to nitrobenzene; blue skin color to nitrates. The most common tip-off is a dark pink or cherry color in the skin or tissue suggesting carbon monoxide poisoning. Carbon monoxide is attracted to hemoglobin, the oxygen-carrying substance in red blood cells. The poison lowers the oxygen-carrying capacity of blood and saturates the hemoglobin, causing that dark hue in the skin. But it’s a tricky game—redness can also suggest cyanide, or arsenic when it appears on intestinal tissue.

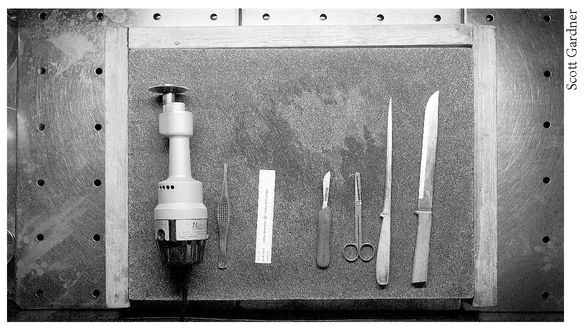

Autopsy tools: electric saw, knives, scalpels

King saw on the chart that Parvesh’s medical history included severe headaches, visits to a Hamilton neurologist. But the CT scan had showed nothing irregular. After King removed the skull cap, he severed connections and lifted out the brain. It weighed just over a kilogram. There was no bruising, no abrasions. He placed the brain in fixing solution. He wanted to retain it for closer examination, even after the body had been returned to the family for cremation. It was an unusual step, as the brain isn’t usually kept after the autopsy. But he was reaching for an answer now. Even with Parvesh Dhillon’s body open before him, he had none.

Other books

Escupiré sobre vuestra tumba by Boris Vian

The Medium by Noëlle Sickels

Doctor Zhivago by Boris Leonidovich Pasternak

November Surprise by Laurel Osterkamp

Why We Took the Car by Wolfgang Herrndorf

Revel by Maurissa Guibord

The Italian Renaissance by Peter Burke

Oy!: The Ultimate Book of Jewish Jokes by David Minkoff

LovePlay by Diana Palmer

Cezanne's Quarry by Barbara Pope