The Definitive Book of Body Language (54 page)

Read The Definitive Book of Body Language Online

Authors: Barbara Pease,Allan Pease

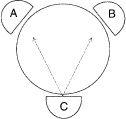

Let's assume that you, person C, are going to talk with persons A and B, and that you are all sitting in a triangular position at a round table. Assume that person A is talkative and asks many questions and that person B remains silent throughout. When A asks you a question, how can you answer him and carry on a conversation without making B feel excluded? Use this simple but effective inclusion technique: when A asks a question, look at him as you begin to answer, then turn your head toward B, then back to A, then to B again until you make your final statement, looking finally at A again as you finish your sentence.

This technique lets B feel involved in the conversation and is particularly useful if you need to have B on your side with you.

Keeping both parties involved when answering a question

On a rectangular table, it seems to be a cross-cultural norm that position A has always commanded the most influence, even when all people at the table are of equal status. In a meeting of people of equal status the person sitting at position A will have the most influence, assuming that he doesn't have his back to the door.

Power Positions at a rectangular table

If As back was facing the door, the person seated at B would be the most influential and would be strong competition for A. Strodtbeck and Hook set up some experimental jury deliberations, which revealed that the person sitting at the head position was chosen significantly more often as the leader, particularly if that person was perceived as being from a high economic class. Assuming that A was in the best power position, person B has the next most authority, then D, then C. Positions A and B are perceived as being task-oriented, while position D is seen as being occupied by an emotional leader, often a woman, who is concerned about group relationships and getting people to participate. This information makes it possible to influence power plays at meetings by placing name badges on the seats stating where you want each person to sit. This gives you a degree of control over what happens in the meeting.

Researchers at the University of Oregon determined that people can retain up to three times more information about things they see in their right visual field than they do in their left. Their study suggests that you are likely to have a “better side” to your face when you are presenting information to others. According to this research your better side is your left because it's in the other person's right visual field.

Studies show that the left side of your face

is the best side for giving a presentation.

Dr. John Kershner of Ontario Institute for Studies in Education studied teachers and recorded where they were looking every thirty seconds for fifteen minutes. He found that teachers almost ignore the pupils on their right. The study showed that teachers looked straight ahead 44 percent of the time, to the left 39 percent of the time, and to their right only 17 percent of the time. He also found that pupils who sat on the left performed better in spelling tests than those on the right and those on the left were picked on less than those on the right. Our research found that more business deals are made when a salesperson sits to the customer's left than to their right. So, when you send children to school, teach them to jockey for the teacher's left side but, when they become adults and attend meetings, tell them to go for the extra perceived power given to the person on their boss's right.

The shape of a family dining-room table can give a clue to the power distribution in that family, assuming that the dining room could have accommodated a table of any shape and that the table shape was selected after considerable thought. “Open” families go for round tables, “closed” families select square tables, and “authoritative” types select rectangular tables.

Next time you have a dinner party, try this experiment: place the shyest, most introverted guest at the head of the table, farthest from the door with their back to a wall. You will be amazed to see how simply placing a person in a powerful seating position encourages them to begin to talk more often and with more authority and how others will also pay more attention to them.

The Books of Lists—

a volume that lists each year all sorts of information about human behavior—shows public speaking as

our number-one fear, with fear of death ranking, on average, at number seven. Does this mean that, if you're at a funeral, you're better off being in the coffin than reading the eulogy?

If you are asked to address an audience at any time, it's important to understand how an audience receives and retains information. First, never tell the audience you feel nervous or overawed—they'll start looking for nervous body language and will be sure to find it. They'll never suspect you're nervous unless you tell them. Second, use confidence gestures as you speak, even if you're feeling terrified. Use Steeple gestures, open and closed palm positions, occasional Protruding Thumbs, and keep your arms unfolded. Avoid pointing at the audience, arm crossing, face touching, and lectern gripping. Studies show that people who sit in the front row learn and retain more than others in the audience, partially because those in the front row are keener than others to learn and they show more attention to the speaker in order to avoid being picked on.

People who sit in the front rows learn more

,

participate more, and are more enthusiastic.

Those in the middle sections are the next most attentive and ask the most questions, as the middle section is considered a safe area, surrounded by others. The side areas and back are the least responsive and attentive. When you stand to the audience's left—the right side of the stage—your information will have a stronger effect on the right brain hemisphere of your audience's brains, which is the emotional side in most people. Standing to the audience's right—the left side of stage—impacts the audience's left brain hemisphere. This is why an audience will laugh more and laugh longer when you use humor and stand to the left side of the stage, and they respond better to emotional pleas and stories when you deliver them from the right side of the stage. Comedians have known this for decades—make them laugh from the left and cry from the right.

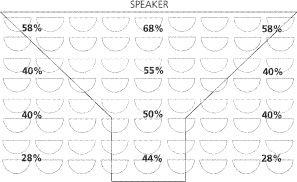

Using parameters by researchers Robert Sommer and Adams and Biddle, we conducted a study of audiences to estimate how much participation was given by delegates based on where they were sitting in a seminar room and how much they could recall of what the presenter was saying. Our results were remarkably similar to the original Robert Sommer study, even though our participants were adults and Sommer's were students. We also found few cultural differences between Australians, Singaporeans, South Africans, Germans, Brits, French, or Finns. High-status individuals sit in the front row in most places—most notably in Japan—and they participate the least, so we recorded audience data only where delegates were generally of equal status. The result was what we call the “Funnel Effect.”

Retention of information and participation by attendees based

on their choice of seat (Pease, 1986)

As you can see, when participants are sitting in classroom style, there is a “learning zone” shaped like a funnel, which extends directly down the center of an audience and across the front row. Those sitting in the funnel gave the most amount of participation, interacted most with the presenter, and had the highest recall about what was being discussed. Those who participated the least sat in the back or to the sides, tended to be

more negative or confrontational, and had the lowest recall. The rear positions also allow a delegate a greater opportunity to doodle, sleep, or escape.

We know that people who are most enthusiastic to learn choose to sit closest to the front and those who are least enthusiastic sit in the back or to the sides. We conducted a further experiment to determine whether the Funnel Effect was a result of where people chose to sit, based on their interest in the topic, or whether the seat a person sat in affected their participation and retention. We did this by placing name cards on delegates' seats so they could not take their usual positions. We intentionally sat enthusiastic people to the sides and back of the room and well-known back-row hermits in the front. We found that this strategy not only increased the participation and recall of the normally negative delegates who sat up front, it

decreased

the participation and recall of the usually positive delegates who had been relegated to the back. This highlights a clear teaching strategy—if you want someone really to get the message, put them in the front row. Some presenters and trainers have abandoned the “classroom style” meeting concept for training smaller groups and replaced it with the “horseshoe” or “open-square” arrangement because evidence suggests that this produces more participation and better recall as a result of the increased eye contact between all attendees and the speaker.

Bearing in mind what has already been said about human territories and the use of square, rectangular, and round tables, let's consider the dynamics of going to a restaurant for a meal, but where your objective is to get a favorable response to a proposition.

If you are going to do business over dinner, it's a wise strategy to complete most of the conversation before the food arrives. Once everyone starts eating, the conversation can come to a standstill and alcohol dulls the brain. After you've eaten, the stomach takes blood away from the brain to help digestion, making it harder for people to think clearly. While some men hope to achieve these types of effects with a woman on a date, it can be disastrous in business. Present your proposals while everyone is mentally alert.

No one ever makes a decision with their mouth full.

A hundred thousand years ago, ancestral man would return with his kill at the end of a hunting day and he and his group would share it inside a communal cave. A fire was lit at the entrance to the cave to ward off predators and to provide warmth. Each caveman sat with his back against the wall of the cave to avoid the possibility of being attacked from behind while he was engrossed in eating his meal. The only sounds that were heard were the gnashing and gnawing of teeth and the crackle of the fire. This ancient process of food sharing around an open fire at dusk was the beginning of a social event that modern man re-enacts at barbecues, cookouts, and dinner parties. Modern man also reacts and behaves at these events in much the same way as he did over a hundred thousand years ago.