You Must Change Your Life (38 page)

Read You Must Change Your Life Online

Authors: Rachel Corbett

After the war, Baladine Klossowska, a German citizen, was forced to leave Paris. She settled in Geneva and separated from her husband in 1917. Two years later, Rilke looked her up while he was in town giving a reading. His five-day visit stretched into fifteen as the old friends speedily became lovers.

Soon they were writing each other letters three times a day and, by the summer of 1921, they began renovating a home together. Set atop a steep cliff in the Rhône Valley, the thirteenth century chateau known as Muzot was a sturdy stone square, as if a castle had collapsed and only one defensive tower remained. Its violetish gray walls

and turrets were reminiscent of a Cézanne mountain, while its barren interiorsâcrumbling stone walls and no water or electricityâwould have pleased Rodin.

Rilke became an adoring and protective father figure to Klossowska's two boys, who were both budding young artists. The eldest, Pierre, was a writer, while little Balthasar was just eleven and already a gifted artist. When Balthasar, a tall, lanky troublemaker, was denied entry into an advanced class at school, Rilke protested to the headmaster that it was not the boy's grades that were at fault, but rather the “extreme pedantry on the part of the school.”

At some point, a stray Angora cat wandered into the house and joined the family, too. They it named Mitsou and it became Balthasar's closest companion. When it ran away one day, the boy drew a series of forty thick-lined ink drawings that illustrated the memories they had shared. They slept together, ate together, spent Christmas together. The final image was a self-portrait of Balthasar wiping away his tears.

Rilke was stunned by the raw skill and vulnerability of the drawings. He found them to be so good, in fact, that he arranged to have them published in a book. They titled it

Mitsou

and Balthasar took Rilke's advice and signed it with his nickname, Balthus, an alias that stuck with the artist throughout his long career as one of modern art's most celebrated and provocative painters.

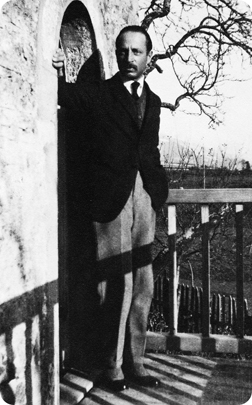

Rilke, a young Balthus and Baladine Klossowska in Switzerland

.

Rilke supplied the foreword to the book, a meditation on the elusive nature of cats and his first text published in French. It opened with a question, “Does anyone know cats?” Unlike dogs, whose unflinching worship for humans feels both wonderful and tragic, “Cats are just that: cats. And their world is utterly, through and through, a cat's world. You think they look at us?” Hardly, he says; even as their eyes are upon us they are already forgetting we exist.

After the book came out, Kurt Wolff, the first publisher of Franz Kafka, came across it and called the drawings “astounding and almost frightening.” And the Postimpressionist painter Pierre Bonnard wrote to “Madame” Rilke with a letter “full of praise” for

Mitsou

. It is no wonder that in all the years after Balthus rose to fame he continued to praise Rilke. He was “a wonderful manâfascinating. He had a wonderful head, with enormous blue eyes. He had a sort of dreamy voice and an extraordinary charm.”

The poet had always treated the boy as an equal. Of one series of drawings, Rilke told the twelve-year-old, “Their invention is charming, and their facility proves the wealth of your inner vision; the arrangement unfailingly enhances the excellent choice you have made.” Given the chance to look at them side by side, he imagined the two artists would share “an entirely parallel, virtually identical joy.”

After

Mitsou

came out, Rilke shut himself up in Muzot for a long, cold winter, and, in February 1922, he wrote all fifty-five of his

Sonnets to Orpheus

. The book was inspired by the death of his daughter's teenage friend Wera Knoop, a dancer who had turned to music after leukemia had ravaged her body. Like the

Elegies

, Rilke said the

Sonnets

came to him almost unconsciously. Critics would later classify the

Sonnets

as the crossroads that guided Rilke to his most mature poetic phase. But to him they were merely the spiritual overflow of the

Elegies

, which he also completed in one final “storm of spirit” that year.

That spring, his daughter Ruth married a young lawyer named

Carl Sieber. Rilke missed the wedding and never met her husband. “I have a great desire to do nothing,” Rilke told Balthus around this time. “If you imagine that an evil sorcerer changed me into a turtle, you'd be close to the reality: I wear a strong and solid shell of indifference toward any challenge.”

Klossowska found him increasingly absent from her life, too. The couple stayed together for five years, but he insisted on spending much of the time away or locked in solitude. She took his absences hard. “But we are human beings, René,” she said to him upon one of his many departures. Eventually Klossowska found herself unable to make a living on her paintingâRilke apparently did not helpâand she took the boys to Berlin to stay with her sister. They lived between Germany and Switzerland for the next two years, with Klossowska updating Rilke often on Balthus's progress. “He's beginning to have a public,” she wrote. “René, he'll be a great painter, you'll see . . .”

Although Rilke's relationship with Klossowska ended in much the same way it had with other women, with Rilke choosing solitude over intimacy, he remained a zealous supporter of her sons. When Pierre Klossowki turned eighteen, Rilke secured him a job working as a secretary for Gide in Paris and assisting him on his novel

The Counterfeiters

. Rilke inquired to his friend endlessly about how much money the boy would need, what he should study and what kind of work he should aspire to do. Eventually Pierre went on to write influential books on Nietzsche and the Marquis de Sade, to translate Kafka, and become a painter in his own right.

Around the same time, Rilke suggested that Balthus, then sixteen, should go to Paris, too. Like Rilke, the young painter would end up forgoing school and letting the city be his teacher. He had already received recognition incredibly early thanks to

Mitsou

. Rilke gave Balthus a copy of Wilhelm Worringer's history of panel painting and sent him off to Paris, also in the care of Gide.

In January 1925, Rilke dedicated his newest poem to Balthus. Titled “Narcissus,” it reimagines a sixteen-year-old boy's extreme self-regard as a condition for his artistic awakening. That fall, Balthus spent all his

days in the Louvre copying Nicolas Poussin's painting

Echo and Narcissus

, incorporating his dedication, à René, onto the surface of a stone.

Throughout Balthus's career, the early themes from his life with Rilke manifested in his work. He became notorious for his almost single-minded focus on painting cats, and on girls who lounged languorously like cats. His biographer Nicholas Fox Weber wrote that Balthus came to identify himself with the feline spirit as a young man, emanating in life and self-portraiture “the same haughty confidence and inaccessibility.” He sometimes signed his work, “H.M. The King of Cats.”

Another dominant motif in Balthus's work was windowsâoften with women falling or gazing out of them. The window was the place in the house where Balthus's mother spent much of her time as she waited for Rilke to return. She decorated the sill with flower boxes to greet him upon his arrival, and to give her something to look at while she sat there. Sometimes his absence would last so long that she would watch the buds bloom and then wither and die before he came back. For Klossowska, Rilke's comings and goings were as fleeting and unpredictable as a cat's.

Rilke had been fascinated by windows since he and Klossowska took a trip to a small Swiss town early in their relationship. He thought about how all the windows of the little cottages looked like picture frames for the lives taking place inside. Someday he'd like to write a book about windows, he said. He never got that far, but he did write a cycle of poems, “Windows,” which Klossowska illustrated. In it, windows become many things for Rilke: they are eyes, a frame of vision, a measurement of expectations. Windows were an invitation, tempting you to come closer, but also an invitation to fall; they could be the beginning of terror. “She was in a window mood that day,” begins one poem, “to live seemed no more than to stare.” Klossowska published them in a little book,

Windows

, a year after Rilke died.

Windows also communicated the essence of the term

Weltinnenraum

, or “worldinnerspace.” Rilke coined the word in his later years to describe the space where the barriers between the internal and external

collapsed onto a single plane. It is a realm where the self is like a bird flying soundlessly between the sky and the soul, he said. Rilke accepts the concept as both a contradiction and a reality in a poem titled “Worldinnerspace”: “. . . O, wanting to grow, / I look out, and the tree grows

in

me,” he writes. Worldinnerspace returned Rilke to the philosophy education that began three decades earlier in Munich. His old aesthetics professor Theodor Lipps might have appreciated the idea while he was trying to explain how it felt to watch dancers whose movements seemed to occur both onstage and in his own muscles.

Rilke at the Chateau du Muzot in Switzerland, 1923

.

This in-between realm was the only place Rilke understood as home, the space where all things came to settle at last. For him, the house was a container and he was the air slipping out its windows; the cat running away at night. He was a ghost and a myth, first of a dead sister and then, at last, as the author of his own death, for which he created a final perfect metaphor.

Â

ONE OCTOBER DAY

in 1926 Rilke pricked his finger on the thorn of a rose as he was gathering a bouquet from his garden. The wound worsened as the days wore on. A septic infection spread into his arm and then to the other arm before invading his entire body. Bloody black blisters erupted on his skin and ulcers flared from the front of his mouth down to his esophagus, making it impossible to quench his desperate thirst. By December, he knew he was nearing the end.

On his last day of life, Rilke asked his doctor to hold his hand, and to squeeze it from time to time. If he was awake, he would squeeze back. If not, the doctor should sit him upright in bed to return him to the “frontier of consciousness.” Rilke did not fear illness, a place he knew well from his youth, nor did he fear death.

Death was simply the laying out of a life. It was the transformation of a conscious being into purely physical matter, which would at least provide conclusive evidence that the person had been realâa fact that was not always self-evident to the poet. To Rilke, death was a “thing” to be examined like any other thing. In “The Death of the Poet,” a poem he'd written shortly after his father died, in 1906, Rilke had described the face of the dead: “tender and open, has no more resistance, / than a fruit's flesh spoiling in the air.” Now it was his own death to which he was to bear witness.

After seeing how much the fear of death had diminished Rodin at the end of his life, Rilke now believed that the only way to face the indignity of his disease was to embrace it. In his bedside notebook, Rilke summoned it like a spirit, beginning his final poem, “Come, you last thing, which I acknowledge . . .” At the end of the page, he made a note to himself to be sure to distinguish this final “renunciation” of death from his childhood sicknesses. “Don't mix those early marvels into this,” he wrote.

Up until his last hour, Rilke refused painkillers. He refused hospitals, where people died en masse. He refused company, including his wife and daughter. He refused to know the name of his disease. He had

already decided it was the poisonous roseâand his death would be his own. When it came on December 29, 1926, three weeks after his fifty-first birthday, he met it with his eyes wide open.

Rilke had his final words etched into his tombstone: “Rose, O pure contradiction, desire to be no one's sleep beneath so many lids.” And when the ground unfroze that spring, the roses awoke, undaunted by the headstone bearing down upon the soil. They gathered around the stone, their young petals opening gently around sleeping, oblivious centers, like mouths and eyelids, ready to receive.