The Definitive Book of Body Language (18 page)

Read The Definitive Book of Body Language Online

Authors: Barbara Pease,Allan Pease

You'd also be stunned when you go to shake hands to say good-bye to an Italian but, instead, you get a kiss on both cheeks.

“As I departed, the Italian man kissed me on both cheeks.

I was tying my shoelaces at the time.”

WOODY ALLEN

As you talk with local Italians, they seem to stand in your space, continually grabbing you, talking over the top of you, yelling, in fact, and sounding angry about everything. But these things are a normal part of everyday friendly Italian communication. Not all things in all cultures mean the same things.

How aware are you of cultural differences in body language? Try this exercise—hold up your main hand to display the number five—do it now. Now change it to the number two. If you're Anglo-Saxon, there's a 96 percent chance you'll be holding up your middle and index fingers. If you're European, there's a 94 percent chance you'll be holding up your thumb and index finger. Europeans start counting with the number one on thumb, two on the index finger, three on the middle finger, and so on. Anglo-Saxons count number one on the index finger, two on the middle finger and finish with five on the thumb.

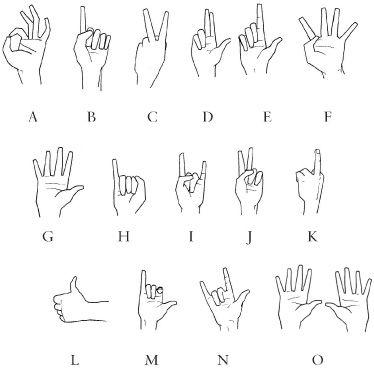

Now look at the following hand signals and see how many different meanings you can assign to each one. For each correct answer, score one point and deduct one point for an incorrect answer. The answers are listed at the bottom of the page.

For each correct answer you get, allocate yourself one point.

A. Europe and North America

: OK

Mediterranean region, Russia, Brazil, Turkey

: An orifice

signal; sexual insult; gay man

Tunisia, France, Belgium

: Zero; worthless

Japan

: Money; coins

B. Western countries

: One; Excuse me!; As God is my witness; No! (to children)

C. Britain, Australia, New Zealand, Malta

: Up yours!

U.S.A.

: Two

Germany

: Victory

France

: Peace

Ancient Rome

: Julius Caesar ordering five beers

D. Europe

: Three

Catholic countries

: A blessing

E. Europe

: Two

Britain, Australia, New Zealand

: One

U.S.A.

: Waiter!

Japan

: An insult

F. Western countries

: Four

Japan

: An insult

G. Western countries

: five

Everywhere

: Stop!

Greece and Turkey

: Go to hell!

H. Mediterranean

: Small penis

Bali

: Bad

Japan

: Woman South America: Thin

France

: You can't fool me!

I. Mediterranean

: Your wife is being unfaithful

Malta and Italy

: Protection against the Evil Eye (when pointed)

South America

: Protection against bad luck (when rotated)

U.S.A.

: Texas University Logo, Texas Longhorn Football Team

J. Greece

: Go to hell!

The West

: Two

K. Ancient Rome

: Up yours!

U.S.A.

: Sit on this! Screw you!

L. Europe

: One

Australia

: Sit on this! (upward jerk)

Widespread

: Hitchhike; good; OK

Greece

: Up yours! (thrust forward)

Japan

: Man; five

M. Hawaii

: Hang loose

Holland

: Do you want a drink?

N. U.S.A.

: I love you

O. The West

: Ten; I surrender

Greece

: Up Yours—twice!

Widespread

: I'm telling the truth

What did you score?

Over 30 points

: You are a well-traveled, well-rounded, broad-thinking person who gets on well with everyone regardless of where they are from. People love you.

15-30 points

: You have a basic awareness that others behave differently from you and, with dedicated practice, you can improve the understanding you currently have.

15 points or less

: You think everyone thinks like you do. You should never be issued a passport or even be allowed out of the house. You have little concept that the rest of the world is different from you and you think that it's always the same time and season all over the world. You are probably an American.

Due to the wide distribution of American television and movies, the younger generations of all cultures are developing a generic form of North American body language. For example, Australians in their sixties will identify the British Two-Fingers-Up gesture as an insult, whereas an Australian teenager is more likely to read it as the number two and will recognize the American Middle-Finger-Raised as a main form of insult. Most countries now recognize the Ring gesture as meaning “OK,” even if it's not traditionally used locally. Young children

in every country that has television now wear baseball caps backward and shout “Hasta la vista, baby,” even if they don't understand Spanish.

American television is the prime reason cultural

body-language differences are disappearing.

The word “toilet” is also slowly disappearing from the English language because North Americans, who are rugged pioneers and log splitters, are terrified to say it. North Americans will ask for the “bathroom,” which, in many parts of Europe, contains a bath. Or they ask for a “restroom” and are taken to where there are lounge seats to relax. In England, a “powder room” contains a mirror and washbasin, a “little girls' room” is found in a kindergarten, and “comfort stations” are positioned on the motorways of Europe. And a North American who asks to “wash up” is likely to be gleefully led to the kitchen, given a tea towel, and invited to wash the dishes.

As discussed in Chapter 3, facial expressions and smiles register the same meanings to people almost everywhere. Paul Ekman of the University of California, San Francisco, showed photographs of the emotions of happiness, anger, fear, sadness, disgust, and surprise to people in twenty-one different cultures and found that in

every

case, the majority in each country agreed about the pictures that showed happiness, sadness, and disgust. There was agreement by the majority in twenty out of the twenty-one countries for the surprise expressions; for fear, only nineteen out of twenty-one agreed; and for anger, eighteen out of twenty-one agreed. The only significant cultural difference was with the Japanese, who described the fear photograph as surprise.

Ekman also went to New Guinea to study the South Fore culture

and the Dani people of West Irian who had been isolated from the rest of the world. He recorded the same results, the exception being that, like the Japanese, these cultures could not distinguish fear from surprise.

He filmed these stone-age people enacting these same expressions and then showed them to Americans, who correctly identified them all, proving that the meanings of smiling and facial expressions are universal.

The fact that expressions are inborn in humans was also demonstrated by Dr. Linda Camras from DePaul University in Chicago. She measured Japanese and American infants' facial responses using the Facial Action Coding System (Oster

&c

Rosenstein, 1991). This system allowed researchers to record, separate, and catalog infant facial expressions and they found that both Japanese and American infants displayed exactly the same emotional expressions.

So far in this book we have concentrated on body language that is generally common to most parts of the world. The biggest cultural differences exist mainly in relation to territorial space, eye contact, touch frequency, and insult gestures. The regions that have the greatest number of different local signals are Arab countries, parts of Asia, and Japan. Understanding cultural differences is too big a subject to be covered in one chapter so we'll stick to the basic things that you are likely to see abroad.

If a Saudi man holds another man's hand in

public it's a sign of mutual respect. But don't

do it in Australia, Texas, or Liverpool, England

Handshaking differences can make for some embarrassing and humorous cultural encounters. British, Australian, New Zealander, German, and American colleagues will usually shake hands on meeting, and again on departure. Most European cultures will shake hands with each other several times a day, and some French have been noted to shake hands for up to thirty minutes a day. Indian, Asian, and Arabic cultures may continue to hold your hand when the handshake has ended. Germans and French give one or two firm pumps followed by a short hold, whereas Brits give three to five pumps compared with an American's five to seven pumps. This is hilarious to observe at international conferences where a range of different handshake pumping takes place between surprised delegates. To the Americans, the Germans, with their single pump, seem distant. To the Germans, however, the Americans pump hands as if they are blowing up an airbed.

When it comes to greeting with a cheek kiss, the Scandinavians are happy with a single kiss, the French mostly prefer a double, while the Dutch, Belgians, and Arabs go for a triple kiss. The Australians, New Zealanders, and Americans are continually confused about greeting kisses and bump noses as they fumble their way through a single peck. The Brits either avoid kissing by standing back or will surprise you with a European double kiss. In his book

A View from the Summit

, Sir Edmund Hillary recounts that on reaching the peak of Everest, he faced Sherpa Tenzing Norgay and offered a proper, British, congratulatory handshake. But Norgay leaped forward and hugged and kissed him—the proper congratulations of Tibetans.

When Italians talk they keep their hands held high as a way of holding the floor in a conversation. What seems like affectionate

arm-touching during an Italian conversation is nothing more than a way of stopping the listener from raising his hands and taking the floor. To interrupt an Italian, you must grab his hands in midair and hold them down. As a comparison, the Germans and British look as if they are physically paralyzed when they talk. They are daunted when trying to converse with Italians and French and rarely get an opportunity to speak. French use their forearms and hands when they talk, Italians use their entire arms and body, while the Brits and Germans stand at attention.

When it comes to doing international business, smart attire, excellent references, and a good proposal can all become instantly unstuck by the smallest, most innocent gesture sinking the whole deal. Our research in forty-two countries shows North Americans to be the least culturally sensitive people, with the British coming in a close second. Considering that 86 percent of North Americans don't have a passport, it follows that they would be the most ignorant of international body-language customs. Even George W. Bush had to apply for a passport after becoming President of the United States, so he could travel overseas. The Brits, however, do travel extensively but prefer everyone else to use British body signals, speak English, and serve fish and chips. Most foreign cultures do not expect you to learn their language, but are extremely impressed by the traveler who has taken the time to learn and use local body-language customs. This tells them that you respect their culture.

This gesture relates to pursing the lips to control the face so that facial expressions are reduced and as little emotion as possible is shown. This way the English can give the impression of being in complete emotional control. When Princes Philip, Charles, Harry, and William walked behind the coffin of Diana in 1997, they each held the Stiff-Upper-Lip expression, which,

to many in the non-British world, came across as unemotional about Diana's death.