Penny le Couteur & Jay Burreson (22 page)

Read Penny le Couteur & Jay Burreson Online

Authors: Napoleon's Buttons: How 17 Molecules Changed History

Tags: #Philosophy & Social Aspects, #Science, #General, #World, #Chemistry, #Popular Works, #History

Trinitrophenol (picric acid)

Many different phenols occur in nature. The hot moleculesâcapsaicin from peppers and zingerone from gingerâcan both be classified as phenols, and some of the highly fragrant molecules in spicesâeugenol from cloves and isoeugenol from nutmegâare members of the phenol family.

Capsaicin (left) and zingerone (right). The phenol part of each structure is circled.

Vanillin, the active ingredient in one of our most widely used flavoring compounds, vanilla, is also a phenol, with a very similar structure to that of eugenol and isoeugenol.

Vanillin is present in the dried fermented seedpods from the vanilla orchid (

Vanilla planifolia

), native to the West Indies and Central America but now grown around the world. These long, thin, fragrant seedpods are sold as vanilla beans, and up to 2 percent of their weight can be vanillin. When wine is stored in oak casks, vanillin molecules are leached from the wood, contributing to the changes that constitute the aging process. Chocolate is a mixture containing cacao and vanillin; custards, ice cream, sauces, syrups, cakes, and many other foods depend partly on vanilla for their flavor. Perfumes also incorporate vanillin for its heady and distinctive aroma.

Vanilla planifolia

), native to the West Indies and Central America but now grown around the world. These long, thin, fragrant seedpods are sold as vanilla beans, and up to 2 percent of their weight can be vanillin. When wine is stored in oak casks, vanillin molecules are leached from the wood, contributing to the changes that constitute the aging process. Chocolate is a mixture containing cacao and vanillin; custards, ice cream, sauces, syrups, cakes, and many other foods depend partly on vanilla for their flavor. Perfumes also incorporate vanillin for its heady and distinctive aroma.

We are only beginning to understand the unique properties of some naturally occurring members of the phenol family. Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the active ingredient in marijuana, is a phenol found in

Cannabis sativa,

the Indian hemp plant. Marijuana plants have been grown for centuries for the strong fibers found in the stem, which make excellent rope and a coarse cloth, and for the mildly intoxicating, sedative, and hallucinogenic properties of the THC molecule foundâin some cannabis varietiesâin all parts of the plant but most often concentrated in the female flower buds.

Cannabis sativa,

the Indian hemp plant. Marijuana plants have been grown for centuries for the strong fibers found in the stem, which make excellent rope and a coarse cloth, and for the mildly intoxicating, sedative, and hallucinogenic properties of the THC molecule foundâin some cannabis varietiesâin all parts of the plant but most often concentrated in the female flower buds.

Tetrahydrocannabinol, the active ingredient of marijuana

Medicinal use of the tetrahydrocannabinol in marijuana to treat nausea, pain, and loss of appetite in patients suffering from cancer, AIDS, and other illnesses is now permitted in some states and countries.

Naturally occurring phenols often have two or more OH groups attached to the benzene ring. Gossypol is a toxic compound, classified as a polyphenol because it has six OH groups on four different benzene rings.

The gossypol molecule. The six phenol (OH) groups are indicated by arrows.

Extracted from seeds of the cotton plant, gossypol has been shown to be effective in suppressing sperm production in men, making it a possible candidate for a male chemical birth control method. The social implications of such a contraceptive could be significant.

The molecule with the complicated name of epigallocatechin-3-gallate, found in green tea, has even more phenolic OH groups.

The epigallocatechin-3-gallate molecule in green tea has eight phenolic groups.

It has recently been credited with providing protection against various types of cancer. Other studies have shown that polyphenolic compounds in red wine inhibit the production of a substance that is a factor in hardening of the arteries, possibly explaining why in countries where a lot of red wine is consumed there is a lower incidence of heart disease, despite a diet rich in butter, cheese, and other foods high in animal fat.

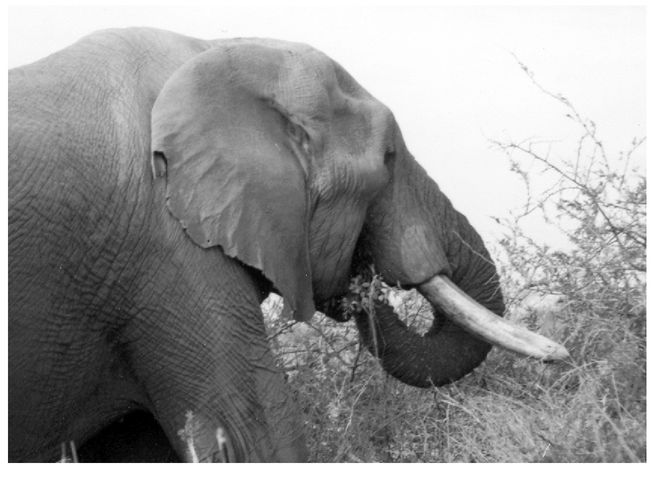

PHENOL IN PLASTICSAs valuable as the many different derivatives of phenol are, however, it is the parent compound, phenol itself, that has brought about the greatest changes in our world. As useful and influential as the phenol molecule was in the development of antiseptic surgery, it had a vastly different and possibly even more important role in the growth of an entirely new industry. Around the same time Lister was experimenting with carbolic acid, the use of ivory from animals for items as diverse as combs and cutlery, buttons and boxes, chessmen and piano keys was rapidly increasing. As more and more elephants were killed for their tusks, ivory was becoming scarce and expensive. Concern for the reduction of the elephant population was most noticeable in the United States, not for the conservationist reasons that we espouse today but because of the exploding popularity of the game of billiards. Billiard balls require extremely high-quality ivory for the ball to roll true. They must be cut from the very center of a flaw-free animal tusk, and only one out of every fifty tusks provides the consistent density necessary.

In the last decades of the nineteenth century, as supplies of ivory dwindled, the idea of making an artificial material to replace it appeared sensible. The first artificial billiard balls were made from pressed mixtures of substances such as wood pulp, bone dust, and soluble cotton paste impregnated by or coated with a hard resin. The main component of these resins was cellulose, often a nitrated form of cellulose. A later and more sophisticated version used the cellulose-based polymer celluloid. The hardness and density of celluloid could be controlled during the manufacturing process. Celluloid was the first

thermoplastic

materialâthat is, one that could be melted and remolded many times in a process that was the forerunner of the modern injection-molding machine, a method of repeatedly reproducing objects inexpensively with unskilled labor.

thermoplastic

materialâthat is, one that could be melted and remolded many times in a process that was the forerunner of the modern injection-molding machine, a method of repeatedly reproducing objects inexpensively with unskilled labor.

A major problem with cellulose-based polymers is their flammability and, especially where nitrocellulose is involved, their tendency to explode. There is no record of exploding celluloid billiard balls, but celluloid was a potential safety hazard. In the movie business film was originally composed of a celluloid polymer made from nitrocellulose, using camphor as a plasticizer for improving flexibility. After a disastrous 1897 fire in a movie theater in Paris killed 120 people, projection booths were lined with tin to prevent the spread of fire if the film happened to ignite. This precaution, however, did nothing for the safety of the projectionist.

In the early 1900s, Leo Baekeland, a young Belgian immigrant to the United States, developed the first truly synthetic version of the material we now call

plastic.

This was revolutionary, since varieties of polymers that had been made up to this time had been composed, at least partly, of the naturally occurring material cellulose. With his invention Baekeland initiated the Age of Plastics. A bright and inventive chemist who had obtained his doctorate from the University of Ghent at the age of twenty-one, he could have settled for the security of an academic life. He chose instead to emigrate to the New World, where he believed the opportunities to develop and manufacture his own chemical inventions would be greater.

plastic.

This was revolutionary, since varieties of polymers that had been made up to this time had been composed, at least partly, of the naturally occurring material cellulose. With his invention Baekeland initiated the Age of Plastics. A bright and inventive chemist who had obtained his doctorate from the University of Ghent at the age of twenty-one, he could have settled for the security of an academic life. He chose instead to emigrate to the New World, where he believed the opportunities to develop and manufacture his own chemical inventions would be greater.

A growing scarcity of good quality ivory from elephant tusks was relieved by the development of phenolic resins like Bakelite.

(Photo courtesy Michael Beugger)

(Photo courtesy Michael Beugger)

At first this choice seemed a mistake, as despite working diligently for a few years on a number of possible commercial products, he was on the verge of bankruptcy in 1893. Then, desperate for capital, Baekeland approached George Eastman, the founder of the photographic company Eastman Kodak, with an offer to sell him a new type of photographic paper he had devised. This paper was prepared with a silver chloride emulsion that eliminated the washing and heating steps of image development and boosted light sensitivity to such a level that it could be exposed by artificial light (gaslight in the 1890s). Amateur photographers could thus develop their photographs quickly and easily at home or send them to one of the new processing laboratories opening across the country.

While he was taking the train to meet with Eastman, Baekeland decided he would ask for $50,000 for his new photographic paper, since it was a great improvement over the celluloid product with associated fire hazards that was then being used by Eastman's company. If forced to compromise, Baekeland told himself he would accept no less than $25,000, still a reasonably large amount of money in those days. Eastman was so impressed with Baekeland's photographic paper, however, that he immediately offered him the then-enormous sum of $750,000. A stunned Baekeland accepted and used the money to establish a modern laboratory next to his home.

Other books

Sixkill by Robert B Parker

Confessions of a Five-Chambered Heart by Kiernan, Caitlín R

Dixie Betrayed by David J. Eicher

Escape From Hell by Larry Niven

Aftershock: A Collection of Survivors Tales by Lioudis, Valerie, Lioudis, Kristopher

Love Child by Kat Austen

Improper Proposals by Juliana Ross

What We Keep by Elizabeth Berg

Reluctant Adept: Book Three of A Clairvoyant's Complicated Life by Katherine Bayless